Kevin Goergen is a doctoral researcher at the University of Luxembourg, currently working on Luxembourg’s colonial entanglements from the 1880s to the 1970s. His research primarily focuses on the historical connections between Luxembourg and the colonial Congo. While Luxembourgers have been present in colonies across Africa since the 1880s, most were involved in colonial projects in the Congo Basin. Luxembourg’s colonial past highlights colonialism without colonies – similar to the cases of Switzerland and Scandinavian countries such as Finland – and invites us to consider its meaning in the present day.

In a series of four blog posts, Kevin reflects on his research trip to Kinshasa in November/December 2024. Beyond his archival work at the INACO, he explores how traces of Luxembourg’s colonial history remain visible in the city’s landscape and daily life. His reflections also consider his own position – as a white historian – navigating the complexities of fieldwork in the DRC.

[Part 1] Arriving, Observing, Settling In

After an eight-hour flight from Brussels, I landed at N’Djili Airport just after 7 p.m. The journey to my hotel took nearly half as long as the flight itself, due to heavy rain and even heavier traffic. As we made our way down Boulevard Lumumba, I tried to take in the scenes outside the car window – dimly lit streets bustling with life, the rhythm of the city already asserting itself. My thoughts were interrupted, as they had been on the plane, by curious fellow passengers asking what brought me to Kinshasa. A historian from Luxembourg, focused on colonial history in the Congo Basin, often sparked thought-provoking conversations. The questions about Luxembourg and its historical ties to the Congo were nothing new to me. What began as a historical discussion soon spiralled into a lively exchange about politics, football, and food.

Suddenly, the car came to an abrupt halt; up ahead, two trucks had collided, blocking the road. I checked my phone to pinpoint our location: we were just past the point where the N’Djili River flows beneath the boulevard. Not far from where we were stuck, back in 1953, a Luxembourger had constructed a hotel with a loan from the Société de Crédit au Colonat et à l’Industrie (SCCI). At the time, not only Belgians but also Luxembourgers were eligible for loans to invest in the Belgian colony. This place was one of several I had pinpointed in advance of the trip by cross-referencing historical addresses and archival photographs with historical maps and current satellite images. My aim was to identify tangible traces of Luxembourg’s colonial presence in Kinshasa – not only through archival sources, but also through the city’s physical landscape and the layers of memory embedded within it.

The question of individual and collective memory, however, was not something I could plan for; it was something I had to open myself up to once on the ground. In preparation, I tried to ready myself as thoroughly as possible, fully aware that much would unfold differently. The drive from the airport alone had already made that abundantly clear.

The next morning, I met Pierre Turban Tudi, a PhD candidate at the University of Kinshasa researching the Congolese sugar industry. Through the Congo Research Network, I had been able to establish connections with professors and doctoral researchers in Kinshasa before my journey. Pierre and I had already exchanged messages, and he generously offered to support my research in Kinshasa. His assistance proved invaluable, particularly when it came to navigating the practicalities of field work and the complexities of local bureaucracy.

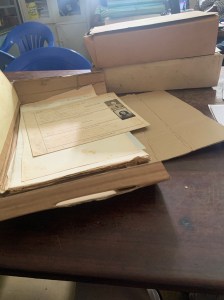

The next day, after taking care of some practical matters – like activating my SIM card – Pierre and I headed to the Institut national des archives du Congo (INACO). I had already called a week earlier to announce my visit. In a relatively small room with several people present, a chair was brought over for me, and I was asked to explain exactly what I was looking for. Since I planned to spend more than a week working in the archives, I opted for a subscription costing $50, which was the more affordable option. I was then given inventories and asked to write down which documents I wished to consult.One of the first documents I examined was a 1950s brochure titled Renseignements à l’usage des personnes nouvellement arrivées au Congo Belge, a guide for white newcomers. It included information on administrative procedures, vaccinations, and other formalities. On the final page, maps listed addresses almost exclusively in the former European quarters of Kalina and Léo-Est – nowadays Gombe. Among them was the “Pâtisserie Nouvelle,” founded by a Luxembourger in 1941 and still operating at the same location today. However, reading the brochure – so clearly shaped by the colonial logic – left me with a strange, mixed feeling. It wasn’t just about how colonialism still linger today, but also something more ‘personal’: how, as a historian, that way of seeing the past is always with you, even when you’re just going through the city. The past isn’t locked away in the archives; it’s right there in everyday histories. To what extend had my perception of the city already been shaped by my research on the colonial period?

My time at the archive proved to be better or easier than I had initially anticipated. After the third day, I decided to continue my visits independently without Pierre. The building was rarely quiet; I was always sharing the space with others. Typically, two to four staff members were present, conversing primarily in Lingala. Although I do not speak the language, I recognized a few words and phrases – often, a single familiar term in a language combined with contextual cues was, as I reckoned, enough to grasp the general meaning. I did my best to adjust to the situation as it unfolded…

While I was immersed in the documents, I occasionally heard my name mentioned and looked up, only to discover that one of the staff members’ sons shared my name. This led to a moment of shared laughter. An initial sense of skepticism – perhaps more my own projection than reality – dissipated by the second day. Conversations became more frequent, and I was able to share more about my research and inquire about additional archival materials that might be relevant to my project.

On the second day, I was granted access to inventories from the colonial archives, particularly those concerning the economy and the white population. Even if access had been granted earlier, it would not have been possible to consult these materials on the first day, as the responsible staff member was absent due to weather-related disruptions.In the days that followed, my work at INACO continued to be shaped by external factors such as power outages and weather conditions. The lack of lighting made it difficult to bring new dossiers into the reading room, while heavy rain and flooded streets prevented those with keys or access to documents from reaching the archives. As a result, the structure of each day remained unpredictable. The only constant was the archive’s closing time: 4:00 p.m.

Discussion

Comments are closed.